Why recognise and reward open research practice?

This introductory section explains the rationale for recognising and rewarding open research in the assessment of researchers, with reference to the open research and responsible research assessment agendas that have evolved in recent years. It can be used as a reference text for a group of stakeholders undertaking a self-assessment exercise using the OR4 maturity framework, and to inform engagement in support of planned action, such as the development of business cases, consultation or co-development with stakeholders, and communications with the wider research community. It can serve to establish a shared understanding of open research and responsible research assessment, and an awareness of the drivers for strategic action in these areas in the higher education and research sector.

Why should open research be part of researcher assessment?

There are key reasons why open research practices are important in the context of researcher assessment:

Open practices support and demonstrate research integrity and quality, by providing transparency about research methods and evidence, and enabling independent verification or reproduction of findings

Open practices generate a variety of outputs in addition to research publications, such as datasets, software and digital resources, and facilitate their re-use, so maximising opportunities to generate further value

The broader range of activities and outputs associated with open research practices enables a more rounded assessment of a researcher’s activities and outputs than is possible where publications are the primary or exclusive focus of assessment.

A researcher who uses open research practices better demonstrates and enables verification of the quality of their research, maximises the potential of their research to generate value, and is able to provide a more representative picture of the totality of their research and related activities.

Operationalisation of open research incentives and expectations in the researcher assessment activities of research-performing organisations will signal that open practices are considered to be an essential part of how research is carried out. It will power the adoption of open research practices by researchers and lead to improvements in research integrity, quality and impact.

UKRI describes open research in the following terms:

Open research, also widely referred to as open science, relates to how research is performed and how knowledge is shared based on the principle that research should be as open as possible. It also enables research to take advantage of digital technology.

Transparency, openness, verification and reproducibility are important features of research and innovation. Open research helps to support and uphold these features across the whole lifecycle of research – improving public value, research integrity, reuse and innovation.

Open research also helps to support collaboration within and across disciplines. It is integral to a healthy research culture and environment.

Open research can be situated in the context of a global discourse about open knowledge and openness in academic practice (which often uses the term open science). In the open knowledge paradigm, ‘openness’ is integral to the practices by which research is conducted, communicated, evaluated, validated and instrumentalised. Open research practice is held to have a direct relationship to research integrity (through transparency of methods and outputs), research quality (through the use of evidentiary and reproducible practices), sustainability (through use of appropriate standards and formats, preservation infrastructure, and persistent identifiers), and reach and impact (through the accessibility and re-usability of outputs).

Open research principles are widely accepted but not fully integrated into research practice

The principles of open research have gained widespread acceptance in recent years, and the importance of openness in research is acknowledged by governments, funders, and research-performing institutions. The 2021 adoption by the UNESCO member states of its Recommendation on Open Science marks a significant milestone in this respect. Many public research funders and most research institutions in the UK have established policies on open access to research publications and the management and sharing of research data, which are fundamental open research practices. More recently, some institutions have adopted statements in support of open research, endorsing the principles and aims of open research and encouraging use of relevant open research practices.

But open research policies and statements are as yet relatively unintegrated into institutional research strategy and planning and actual research practice. Beyond high levels of compliance with open access mandates, driven in large part by the requirements of the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF), there is little evidence of widespread open research practice. Rates of effective data sharing remain low.1 Open research practices are for the most part not incentivised and rewarded; nor, with the exception of open access publication, are they systematically monitored or enforced, either by institutions or by the funders of research.

Systems of reward and recognition can drive changes in researcher behaviour and academic cultures

At present, very few institutional recruitment, promotion, probation and appraisal frameworks include reference to open research criteria or outputs other than research publications; standards and practices for evidencing a track record in open research are not well-established; and there is a lack of guidance, training and support related to open research for researchers and staff involved in assessment. In consequence, use of open research practices is rarely evidenced or considered in the formal assessment activities, and is in large part unmonitored by institutions.2

With momentum for research assessment reform building globally, there is an opportunity to integrate open research into revised researcher assessment frameworks and practices. Universities play a critical role in the systems of academic reward and recognition. It is in their power to include open research criteria in their recruitment specifications, probation objectives and promotion frameworks, performance and development review processes, and research planning activities. By this means researchers can be incentivised and supported to build a track record in open research and to present that track record in an assessment activity, while assessment practices can recognise and give credit for a record of open research practice. This will drive increased adoption of open research practices, and, in time, bear fruit in the recruitment and promotion of staff who are recognised for working in ways that increase the integrity, quality and impact of the institution’s research output.

Open research and research assessment reform

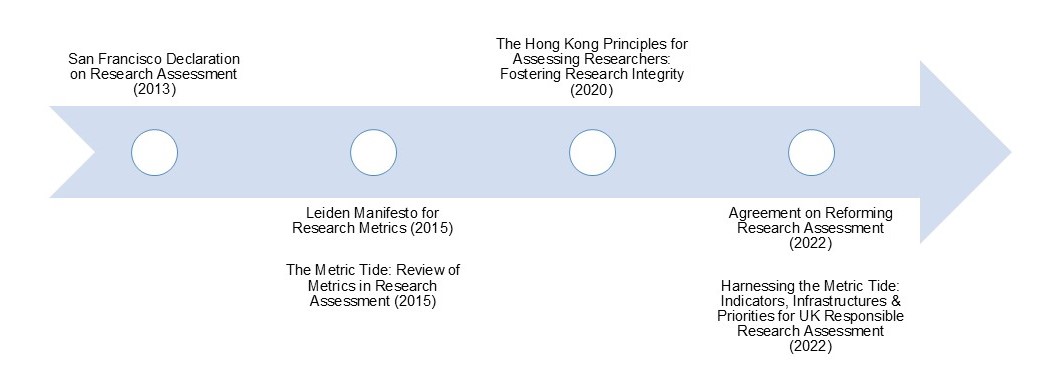

The history of research assessment reform can be characterised in terms of an evolution from an agenda focused almost exclusively on the use of publication-based metrics towards a broader framework of responsible research assessment (Figure 1). This broader, more instrumental agenda considers research assessment as a means of enabling the best researchers to flourish, promoting diversity and inclusion, and supporting the production of high-quality research – in short, as a means to engineer research culture. Within this agenda, there has been growing attention to the role of open research practices in relation to research assessment.

Although the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA, 2013), the founding text of research assessment reform, was primarily concerned with research publications and related metrics, its second recommendation adumbrates a broader assessment agenda:

For the purposes of research assessment, consider the value and impact of all research outputs (including datasets and software) in addition to research publications, and consider a broad range of impact measures including qualitative indicators of research impact, such as influence on policy and practice.

While DORA mentions datasets and software as examples of other research outputs, it lacks the broader concept of open research that has developed in the years since its publication, and does not provide guidance on how other types of output might be included and assessed. The Leiden Manifesto and the Metric Tide report (both published in 2015) were similarly focused on the use of publication metrics.

With the more recent emergence of a broader framework of responsible research assessment,3 there has been increased attention to open research. A white paper from the League of European Universities (LERU) published in 2018 recommended that universities ‘endeavour to integrate Open Science dimensions in their HR and career frameworks as an explicit element in recruitment, performance evaluation and career advancement policies’.4 Also in 2018, the European Universities Association published the ‘EUA Roadmap on Research Assessment in the Transition to Open Science’, which argued:

Today, research assessment and reward systems generally do not reflect important Open Science contributions, such as curating and sharing datasets and collections, documenting and sharing software (source code), or devoting time and energy to high-quality peer review. New approaches to research assessment that take into account Open Science contributions need to be identified and thoroughly discussed by academic communities.5

The ‘Hong Kong Principles for assessing researchers’ (2020) call for assessment to develop a much broader picture of a researcher’s contributions to research and society. It identifies as one of its five principles to ‘Reward the practice of open science (open research)’, and it makes a strong connection between research transparency and research integrity.6 The UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science (2021) also enjoins member states to remove barriers to open science relating to research and career evaluation and awards systems, stating: ‘Assessment of scientific contribution and career progression rewarding good open science practices is needed for operationalization of open science’.

In the Agreement on Reforming Research Assessment, published in 2022 by the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA), ‘openness’ is recognised as being integral to the practices by which research is conducted, communicated and validated, and is identified as a key dimension of research assessment. Under the ‘Quality and impact’ principle of research assessment it states: ‘Openness of research, and results that are verifiable and reproducible where applicable, strongly contribute to quality’. Under the principle ‘Diversity, inclusiveness and collaboration’, signatories agree to:

Consider… the full range of research outputs, such as scientific publications, data, software, models, methods, theories, algorithms, protocols, workflows, exhibitions, strategies, policy contributions, etc., and reward research behaviour underpinning open science practices such as early knowledge and data sharing as well as open collaboration within science and collaboration with societal actors where appropriate.

National and institutional assessment practices need to develop

The greater emphasis on open research in the research assessment reform agenda is relatively recent, and national and institutional research assessment policies have so far reflected a prevailing focus on publications and the responsible use of publication metrics. In a survey undertaken by the OR4 project in 2023, 44 or 73% of 60 UK institutions stated that they had a responsible research assessment statement or policy. The majority of these were focused on the responsible use of publication metrics.7 In scope and terminology many of these statements follow and reference DORA and the Leiden Manifesto.

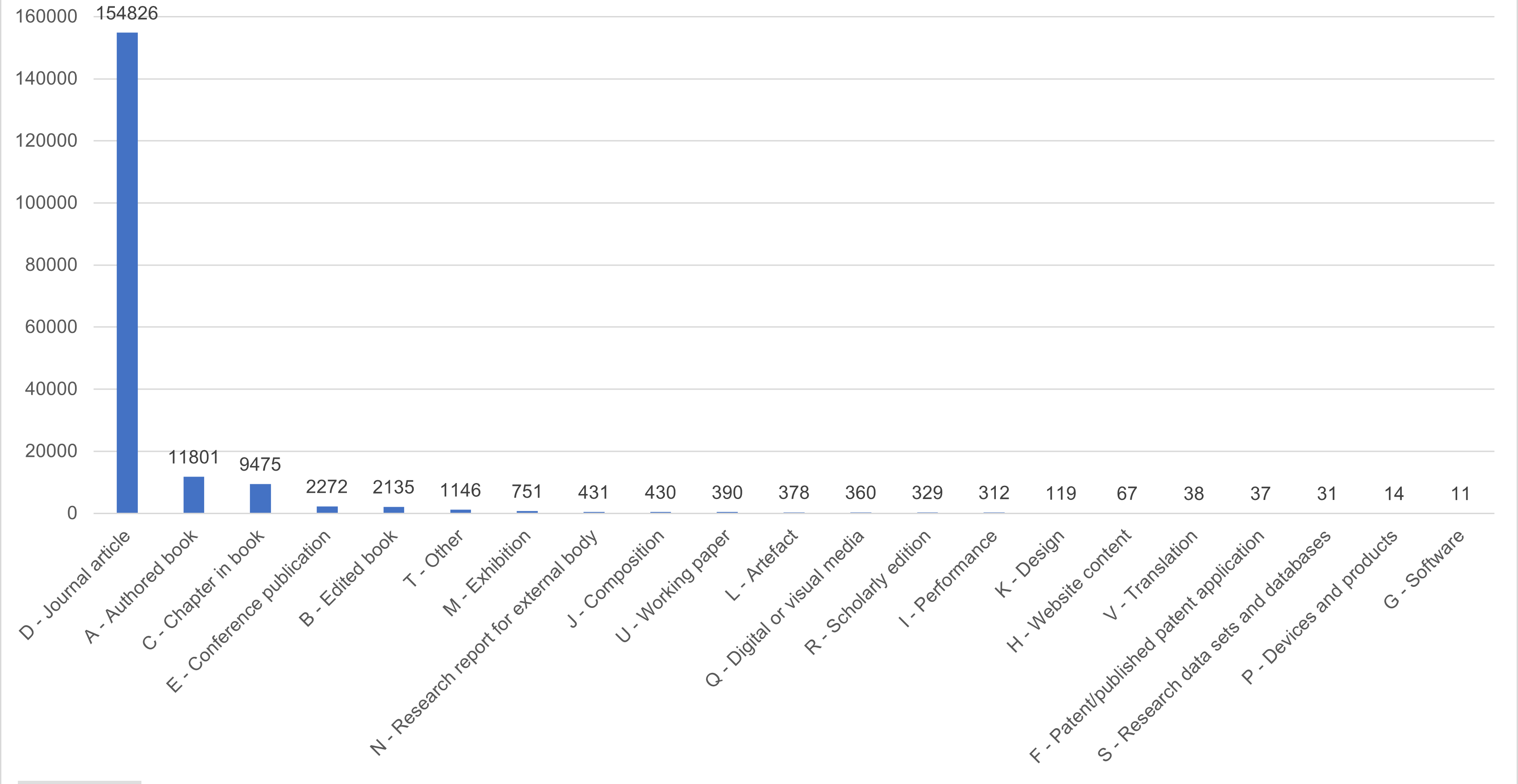

The almost exclusive focus on the assessment of research publications is understandable, given their prominence in the systems of academic recognition and reward. In REF 2021, of 185,353 outputs submitted, 180,509 or 97.4% fell into the main academic publications categories A-E (including authored and edited books, book chapters, journal articles and conference contributions). 154,826 outputs or 83.5% of the total were journal articles. The number of research data sets and databases submitted was 31; the number of software outputs was 11 (Figure 2).8

This heavily skewed distribution is the focus of the Hidden REF initiative, which emerged in the runup to the 2021 REF. This campaign highlighted the lack of representation in submissions for non-academic research contributors (such as data scientists, technicians and research software engineers) and for ‘non-traditional’ outputs (i.e. other than publications). Now that the UK is on track for REF 2029, the Hidden REF is campaigning on a 5% manifesto: a target for HEIs to submit at least 5% of non-traditional research outputs. This will be a challenging target to meet, given that in REF 2021 only 2.4% of non-traditional outputs were submitted.

But the landscape is beginning to change, and institutions will need to develop policies that better align to the principles of responsible research assessment and that are more representative of the full diversity of research and research-related activities and outputs.

Assessment should recognise all contributions to research

Contribution to open research should be recognised and rewarded wherever and by whomever it is made. Institutional policies and practices should be designed inclusively and should recognise the collaborative nature of much research.

As the Hidden REF campaign has highlighted, much research is collaborative in nature and is contributed to and enabled by people in research-performing organisations who are not defined as academic researchers: data scientists, technicians, research software engineers, librarians and others. These contributory and enabling roles are often obscured in the reporting and assessment of research, given the prevailing focus on the publication as the representative research output, and on the academic researcher as the ‘author’ of the research.

The non-traditional outputs which lack visibility within systems of research assessment are also those to which non-academic staff typically most contribute, and as they are rarely named in publications, their role is often occluded in the formal reporting of research and its assessment. If non-traditional/open research outputs such as datasets and software are more visible in the reporting and assessment of research, the hidden contributors to research are also made more visible, and can be better recognised and rewarded in systems of employee assessment. Better recognition of contribution to research also supports a more diverse and inclusive research culture, and insitutional policies should be designed to enable appropriate recognition of contributions to research by non-academic staff.

The changing national and international research assessment environment

In comparison to previous national assessment exercises, REF 2029 places greater emphasis on institutional research culture, including use of open research practices. Institutions can provide evidence of this in the People, Culture and Environment element, while the element Contribution to Knowledge and Understanding enables a greater diversity of research activities and outputs to be evidenced.9

As the national research assessment framework progressively assimilates open research objectives and assessment criteria, institutions will be obliged to conform, and to integrate open research into their own policies, systems and processes. The greater emphasis on open research in the 2029 REF is consistent with international developments, where other national research environments are also beginning to demonstrate greater alignment to the principles embodied in the Agreement on Reforming Research Assessment, and to identify open research as an important element of incentive and reward systems.

In the Netherlands, a 2020 report by the National Programme on Open Science argued that reform was needed on three levels: at the level of national assessment, at the institutional level, and at the level of funding agencies. The roadmap for the Dutch Recognition and Rewards Programme identifies open science as a priority, and aims to ‘clarify how activities relating to open science and open education will be considered and/or prioritised as a topic of discussion in the development, assessment, appointment and promotion of staff’.10 Funding has since been ringfenced by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) to support implementation and stimulation of open science culture and practices.

In 2021 Universities Norway published NOR-CAM, a national research assessment framework that integrates open science principles in the assessment of academic results, activities and competencies. NOR-CAM was developed from the Open Science Career Assessment Matrix (OS-CAM) proposed by the EU Working Group on Rewards under Open Science in 2017.11

The Irish National Action Plan for Open Research published in 2022 calls for an alignment of research assessment with the principles of open research at both national and institutional level as part of action to establish a culture of open research, and proposes among other actions adoption of a modified OS-CAM model to the national context.12

Challenges of including open research in researcher assessment

Ensuring the meaningful inclusion of open research objectives in institutional researcher assessment and aligned research planning activities at all levels in an institution is a long-term challenge requiring a sustained effort of leadership and co-ordinated activity. Challenges can be summarised as political, cultural, practical and operational.

Political

There is substantial institutional investment in the prevailing publication-based model of research assessment. Institutional research KPIs and research elements of league table rankings are largely defined by publication metrics. Not all research leaders, managers, and researchers will agree that use of open research practices is a relevant criterion of research assessment, and securing buy-in to support policy adoption and implementation across relevant procedures may not be straightforward.

Cultural

There will be similar challenges securing engagement and bringing about changes in practice among members of the research community at large, in their capacity as both assessors and subjects of research assessment. Many will not have fully integrated open research practices into their working methods and may have concerns they would be disadvantaged. Care will need to be taken that where open research criteria are introduced in assessment practices their use is fair and equitable. Ability to evidence open research practice will depend on the discipline and type of research, and the background and career stage of a researcher. Researchers may have lacked the training, means or opportunity to use open research practices. All of these factors will necessitate the provision of guidance, training and support in the context of sustained activity to develop and enable a culture of open research practice.

Practical

The institution will need an effective operating definition of open research. Researchers and those involved in the assessment of researchers will need to be equipped to identify activities and outputs that fall under that definition, to make an assessment of the degree to which an activity or output fulfils qualifying criteria, and to appraise the value of the activity or output within the context of the assessment as a whole. Each of these requirements presents its own challenges. Many academics may struggle to identify open outputs, or fail to appreciate the difference between, say, a dataset that is published on a project website without a licence and one that has been deposited in a data repository under an open licence and assigned a DOI.

It is also the case that for many open research outputs there is no pre-publication peer review, and standards of assessment may be difficult to define and apply across a variety of outputs, even of the same type, meaning that outputs often lack markers of certification. It is also often difficult to obtain reliable, comparable quantitative information about the citation and use of many open research outputs, although a number of initiatives are addressing the collection and use of open research indicators and metrics.

Operational

There will be the complex work of implementing changes to policies and procedures, and underpinning systems, processes and support, creating and delivering guidance and training, monitoring compliance with implemented policies and taking follow-up action as required. This may entail development of or addition to existing systems and processes. Systems for management and assessment of research are based in large part on research publications, which are well-defined entities that support citation, quantification and comparison. Mature infrastructure, systems and processes facilitate their dissemination, and the collection and processing of information about them. Models for the integration of open research into institutional research assessment and research planning are yet to be established; but if research assessment is to accommodate a wider range of activities and outputs, this will introduce complexity and additional operational demand.

The OR4 implementation guide addresses these aspects of implementation, with an emphasis on the political and cultural aspects in the earlier sections moving into the practical and operational aspects in the later sections.

Footnotes

See e.g.: Gabelica, M., Bojčić, R. and Puljak, L. (2022), ‘Many researchers were not compliant with their published data sharing statement: a mixed-methods study’. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 150: 33-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.05.019; Lucas-Dominguez, R. et al (2021), ‘The sharing of research data facing the COVID-19 pandemic’. Scientometrics (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03971-6.↩︎

See: Pontika, N. et al. (2021), ‘ON-MERRIT D6.1 Investigating institutional structures of reward & recognition in Open Science & RRI (1.0)’. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5552197; Khan, H. et al. (2022), ‘Open science failed to penetrate academic hiring practices: a cross-sectional study’. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 144: 136-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.12.003.↩︎

‘The focus on responsible metrics has now been folded into the broader framework of responsible research assessment (RRA). This can be defined as “an umbrella term for approaches to assessment which incentivise, reflect and reward the plural characteristics of high-quality research, in support of diverse and inclusive research cultures”.’ Curry, S., Gadd, E. and Wilsdon J. (2022), ‘Harnessing the metric tide: indicators, infrastructures and priorities for responsible research assessment in the UK’. Research on Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21701624.v2, p. 23. The quotation refers to a paper from the Research on Research Institute that is perhaps the first to articulate this broader framework. See Curry, S. et al. (2020). The changing role of funders in responsible research assessment: progress, obstacles and the way ahead (RoRI Working Paper No.3). 10.6084/m9.figshare.13227914.v2. Research on Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13227914.v2↩︎

Ayris, P. et al (2018), ‘Open Science and its role in universities: a roadmap for cultural change’. League of European Research Universities. https://www.leru.org/publications/open-science-and-its-role-in-universities-a-roadmap-for-cultural-change.↩︎

European Universities Association (2018), ‘EUA Roadmap on Research Assessment in the Transition to Open Science’. https://eua.eu/resources/publications/316:eua-roadmap-on-research-assessment-in-the-transition-to-open-science.html.↩︎

Moher, D. et al. (2020). ‘The Hong Kong Principles for assessing researchers: Fostering research integrity’. PLoS Biol 18(7): e3000737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000737.↩︎

Barnett, J. at al. (2024). ‘OR4 Research Assessment Survey Report’. Working Paper No 5. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/z52cn.↩︎

REF 2021 Submitted outputs’ details. https://results2021.ref.ac.uk/outputs.↩︎

Research England (2023), ‘Research Excellence Framework 2028: Initial decisions and issues for further consultation’. https://www.ukri.org/publications/ref2028-initial-decisions-and-issues-for-further-consultation/.↩︎

Hans de Jonge (2023), ‘Open science and recognition & rewards: what’s the link between them?’ Recognition & Rewards: Embrace the Impact. https://recognitionrewardsmagazine.nl/2023/open-science/.↩︎

Working Group on Rewards under Open Science (2017), ‘Evaluation of research careers fully acknowledging Open Science practices’. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/75255.↩︎

NORF (2022). National Action Plan for Open Research. https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.ff36jz222.↩︎